Celestial Pablum #6: Craft

Woodworking, the Division of Labor, the United Electrical Workers, William Blake

A few things—getting into woodworking, trying to grasp what was involved in the Gothic Revival, and thinking about the consequences of industrial society, not only in terms of our combustion-powered plunge into serial catastrophe but of the ways in which the political/ideological solutions for maintaining class domination in an era of mass production and rising democratic pressure (what we can call for short the “consumer society” or what Henri Lefebvre called, with greater precision, the “bureaucratic society of controlled consumption”) create mental habits that themselves preclude graspable alternatives from emerging—have gotten me thinking about the significance of “craft.”

Slight nausea is justified given how easily the term descends into hazy sentimentality. This is craft as fetish, a series of thin aesthetic signposts that evoke ill-defined vibe-notions around honesty and authenticity, whatever those may be. Some have exploited the ambiguities around craft to great effect. The Mast brothers, who melted down industrial chocolate and resold it in suitably precious packaging at a juicy premium while pushing the nineteenth-century-bearded-butcher-man aesthetic to its cartoonish apogee, impress by pushing the scam with such brazenness that it forms its own critique, edging its way into performance art. Real craft production is a more vexing proposition—as this recent Twitter thread illustrates, a rigorous commitment to less-industrial methods is all but impermissible in the contemporary capitalist economy, not because any commissar deems it so but because the dynamics of that economy itself render it impossible to make a living without charging thirty dollars for a mildly ethical hamburger. On the other hand, the salvageable content in the forest of vibes surrounding craft is the way it registers a dissatisfaction with the relentless, mind-erasing tsunami of low-quality objects, produced no one knows where or how, that efface any connection between producer and consumer, draining both of autonomy and meaning while generating wealth in the most profoundly antisocial way yet devised by humans. The attraction to craft production at least whispers this problem. Beneath the aroma of sawdust, then, is there still something worth unpacking about the concept?

Labor historians make a distinction between craft and industrial labor. Each concept has a logic, a history, and a relation to the other. The key concept here is the division of labor, which emerged historically as a response to the efficiency demands created by capitalist competition. Craft labor is distinguished above all by the absence of it. What does the division of labor achieve? Speed—more output, less time. Craft work, which in its ideal sense involves involves one mind and one body conceiving, designing, organizing, and operating in order to generate some kind of result or product, admits a broader range of goals around both the qualities of the final product and the relationship of the worker to the set of activities we call “work.”

Hegel (and Marx) conceived of labor as a “formative” activity that sets in motion the development of both producer (subject) and product (object).1 The problem with the division of labor, which breaks down the work process into the smallest feasible tasks and then compels workers to increase the rate of output through specialization, or the insistent repetition of these limited actions, is that it short-circuits the opportunity for self-development on the part of the worker. In industrial labor, the intellectual work of envisioning, designing, and planning is extracted from the head of the worker and lodged in a stratum of managers who alone possess the privilege of grasping the process as a whole. Industrial labor thus severs the connection between head and hand and between the worker and the final product. Greater output is achieved at the cost of mutilating the minds of the majority of those involved. Craft work maintains these connections and these opportunities. This is why so many people enjoy their hobbies more than their jobs.

In his book Workers in Industrial America, one of two or three books on American labor history I would recommend to someone who only had time for two or three books, the historian David Brody quotes an early-twentieth-century Kentucky miner who explains that “anyone with a weak head and a strong back can load machine coal, but a man has to think and study every day like you was studying a book if he is going to get the best of the coal using only a pick.”2 The statement is evidence that the philosophy of craft work was grasped quite acutely by a lot of the people who did it. But, Brody also notes, this way of working was quickly being eroded by the dynamics of industrialization:

A door closed behind the American worker at the turn of the century. An earlier world of labor, weakening for many years under the impact of America's industrial revolution, had slipped irrevocably into the past, and after 1900 the wage earner stood wholly within the modern industrial order. Only now could he fully take in his fate—what it meant to work in a large-scale, mechanized, rationally managed, corporate system of production. And only now, when it was essentially fixed, had the time arrived for coming to terms with the industrial system.3

This “coming to terms” would take shape in the great wave of unionism that swept American industry in the 1930s, whose success was predicated on a group of organizers who grasped the technical-political consequences of the emergent mass-production society. This phenomenon to which they responded was the general tendency and the case for the majority. At the same time, craft work could not be completely eliminated. Machines might deaden work and ultimately replace the hands that tended them, but their action was not so seamless that the companies could do without a stratum of workers to operate and maintain them. This work required creativity, planning, initiative, and a sense of the relationship between part and whole. And these workers—talented, independent, often bearing the unique intellectual cast of the working-class autodidact, recognizable to anyone who has taught in a public school—formed a relative elite, members of a dwindling clan whose jobs could not yet be dissected, standardized, mechanized, and eliminated. These workers—machinists, toolmakers, patternmakers, less those who operated the machines than those who made the machines operable, and who were as a consequence less easy to replace—became a recognizable type in the waves of militancy and organization that produced modern industrial unionism. They constituted, as historian Ronald Schatz explains, a distinct layer on the shop floor whose intellectual acuity extended beyond technique and into politics:

Although the great majority of machinists, like electrical workers and twentieth-century Americans generally, took little interest in politics, highly skilled machinists who started work during the 1910s and '20s were disproportionately represented in the small left-wing groups active in the electrical industry until the 1950s. These men had chosen a job which was both demanding and high paying and which offered them a greater degree of control over their own work than was common in factories. Yet the differential which separated their pay from that of less skilled workers was narrowing throughout the early twentieth century, while their freedom and power in the workplace was under assault from management's new systems of time-and-motion study and incentive wages. … Faced with these pressures, highly skilled machinists swung to the left, not just in American electrical manufacturing centers, but throughout the industrialized world.4

One of my favorite examples comes from the early history of the United Electrical Workers (UE), a criminally understudied organization whose animating principles embodied what is today called the “rank-and-file approach” to organizing. UE Local 475, the organization’s leftmost flank, was born in the machine shops of New York City, where its earliest cadres consisted of just this breed of skilled machinist. Tom Scanlan, for example, was born in Birmingham, England and emigrated at age 35 to the US, where he became a member of an International Association of Machinists local that vigorously asserted the imperative to organize all workers, regardless of background or skill, while challenging the parent organization’s whites-only policy. Scanlan later became a machinist at the National Fastener Corporation, a zipper manufacturer located in Brooklyn’s Bush Terminal (what is now called “Industry City”), where he served as shop chairman. John “Scotty” Henderson was a Glasgow-born machinist who began work as a locomotive repairman at age fourteen but found himself blacklisted following his participation in the 1919 “Red Clydeside” strikes for the forty-hour week. In New York, Henderson found work at EW Bliss, a machine-tool manufacturer with a massive factory beneath the Manhattan Bridge. Both were allies of James Matles, the Romanian-born machinist and legendary organizer who rose to become the Director of Organization of the UE, which grew to over 600,000 members. In New York City, they helped lead a union local feared for its militancy, one that by the 1950s was 85 percent women and 20 percent African American and Puerto Rican. They were able to do so because they recognized the way that the social dynamics of industrialization were irreversibly transcending the craft outlook. At the same time, it was arguably certain features of that craft outlook that provided them the intellectual breadth to confront what mass production was doing to them and their colleagues.

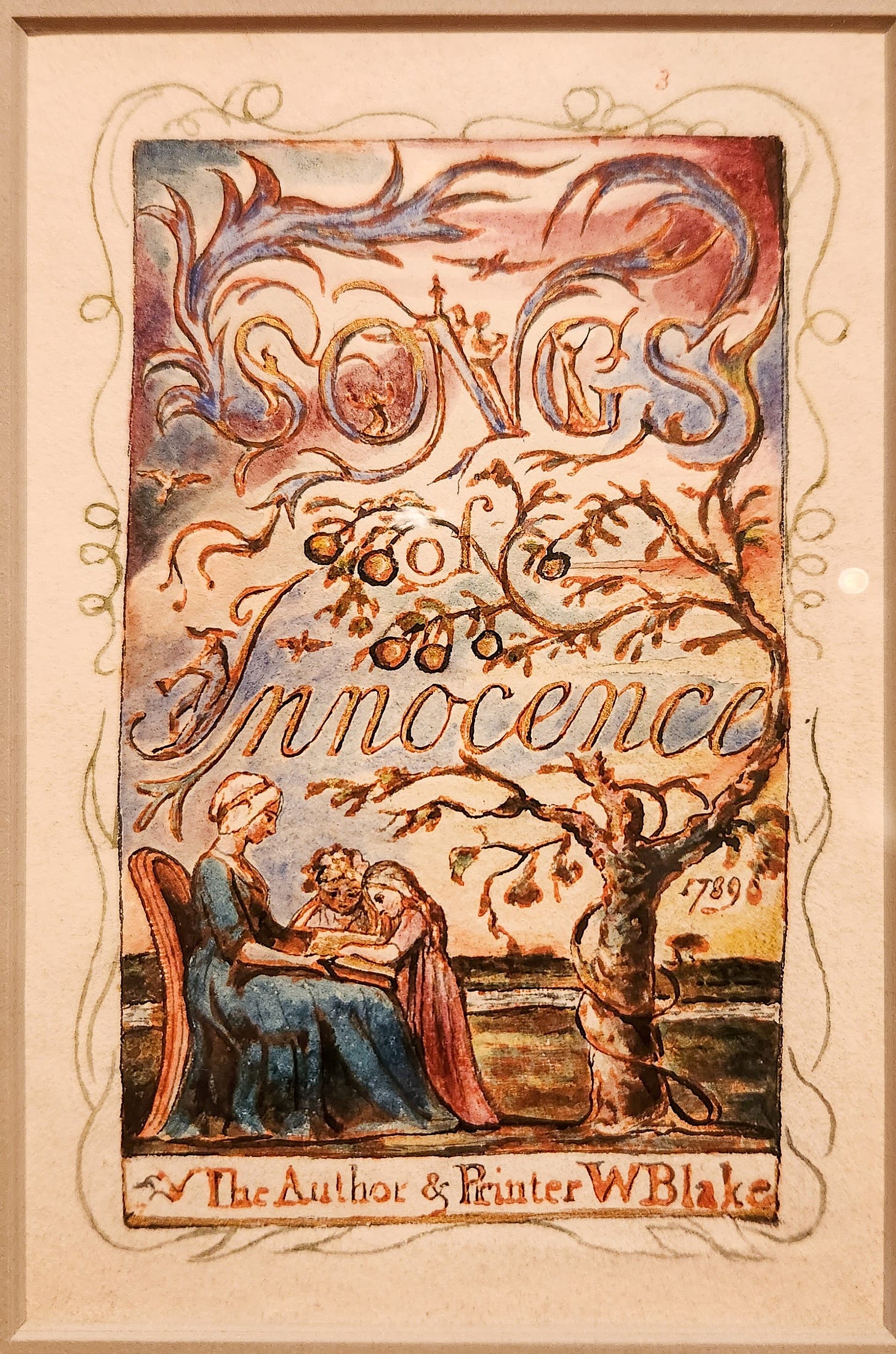

The exhibition of prints from William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience that was recently up at the Met Museum reflects some of the attributes of craft production as well as a throughline to what would come to be called the Gothic Revival, which was less a set of aesthetic conventions than an argument about the politics of work. Blake, as the frontispiece to Songs of Innocence announces, was imagemaker, poet, and printer all in one, combining a set of skills that would later be severed from one another by an emerging division of labor in art-making. The illustrated books he created refuse the the separation between word and image, between reason and feeling. This refusal of narrowness is also a theme of Blake’s poetry—in the scheme of his four zoas, each representing an aspect of a fallen and divided humanity, Los represents the poetic imagination while Urizen, its antithesis, is the avatar of enclosure, the one who weaves a “Web dark and cold,” measuring out everything with ruler and compass, reducing all phenomena to numbers—a god of abstraction. And there was no difference between Blake’s attitude to aesthetics and his attitude to politics. Blake associated Satan with the mechanical materialists—Newton, Locke, and Bacon—whose ideas he saw as consonant with an emerging capitalism, where the factory serves as a model for all of society. As Peter Ackroyd notes in his biography of Blake, the latter “sees the connection between the slaves of Surinam and the women of England, between commerce and sexual brutality, between Lockean theories of sensation and religious orthodoxy, all filaments in the web of the materialist mercantile world.”5

One result of Blake’s way of working is that no two copies of Songs were the same. The irregularity characteristic of handicraft production sometimes appears amateurish to contemporary eyes trained by the ersatz perfection of mechanical reproduction. Grasped another way, though, Blake’s works bear the traces of their material process of creation in ways that mass-produced goods do not. This irregularity, the Victorian critic John Ruskin asserted, embodies the concurrent development of self and object that is the essence of the activity we call labor. Mass production, which demands standardization (to increase output) and machines, which store and deploy, as if by magic, the congealed intelligence and labor of the humans that came before them, abstract from the particular knowledges and skills that craft workers must maintain and deploy, and in so doing, cloak from recipients’ eyes all the thought, decision-making, and manual dexterity lodged, real but invisible, within the product. In this way, a social process comes to appear as an inert thing. At the same time, standardization and mechanization centralize control of the work process in the hands of a small group of managers while robbing workers of the opportunity to grow through experiment and experience. It is for this reason that Ruskin, William Morris, and other partisans of what came to be called the Gothic Revival prioritized hand production, which bears the marks of that experience in the form of that which from the sleeker perspective of the machine appears as bungling imperfection. For Ruskin and Morris, though, what they called the Gothic was somehow truer than industrialized mass production.

It is worth noting that the language of craft production itself preserves this connection between the technical and the moral. Etymologically speaking, the word “true” is a complex denoting a combined sense of honesty, consistency, and certainty. In carpentry and woodworking, a “true” surface is one that has been made sufficiently level and where the angles are ninety degrees, creating the best possible conditions for joining one piece of wood to another. That expressions derived from carpentry, such as “tried and true,” have made their way into unthinking common usage both reveal and conceal a once-uncontroversial connection between head and hand, the philosophical and the material, theoretical understanding and empirical testing. How do you know a surface is true? You try it.

The challenge for any politics that incorporates craft today is how to reintroduce this broader set of principles around productive activity to a society so far down the road of abstraction, commodification, mass production, and their corrosive psychic consequences that it melts the mind beginning to think how one might get “back” (and there is, of course, no going “back” to anything). These are the issues underlying the mostly unedifying debates around whether restaurants will continue to exist in their present form (with presumably higher wages and tolerable working conditions) in a hypothetical future communist society. There is a sort of vulgar version of the “communal luxury” thesis that imagines it could be achieved without dismantling money and wage labor themselves. This narrow, unimaginative social-democratic vision does not grasp that there is an intrinsic connection between the dynamics of wage labor and commodity production and downward pressure on working and living conditions, or that half the punishment of the commodity society lies in the psychic devastation—under which, which for the sake of brevity, we can class every feeling, every contradiction that lodges itself under the umbrella of alienation—written into the very fibers of wage labor as a structuring principle of human creative activity.

In a socialist society, one which takes this transformation of productive relations as its criterion, all work—or whatever new name we give to productive activity—will acquire some of the characteristics of what we now call craft. But are there limits to the degree to which craft production can serve as an adequate foundation for the reproduction of human beings living in the world capitalism has created? Year-zero fantasies, where alienation is abolished by turning people back into animals, are unlikely to become the foundation of movements that have mass appeal. This raises the question, posed by Herbert Marcuse, among others, of whether we can distinguish between “necessary” and “surplus” alienation, of whether some kinds of repression, alienation and objectification are acceptable as the prerequisite for other kinds of freedom. A total, amniotic coincidence between subject and object is neither realistic nor desirable. At the very least, though, grasping the principles of craft forces the qualities we have forfeited as a consequence of mass production into the starkest relief.

Bonus

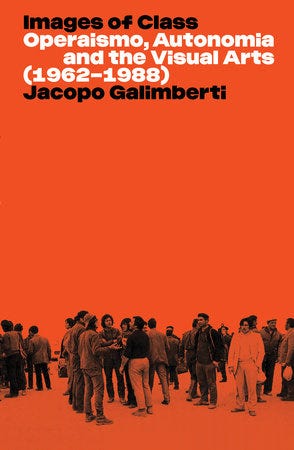

The book of the year so far for me is Jacopo Galimberti’s Images of Class: Operaismo, Autonomia, and the Visual Arts (1962–1988), which broadens for English-language readers the incomparably rich confrontations with political, cultural, and aesthetic questions that emerged from the Italian extra-parliamentary left in the period between the late 1950s, when cracks emerged in the hold of the Stalinist-oriented Italian Communist Party on left-wing thinking in Italy, and the 1980s, which witnessed the final defeat of the movement in a pincer of economic crisis and state repression.

This is a book that serves as a primer on operaismo worthy of being read alongside Steve Wright’s classic Storming Heaven, but one that in its focus on aesthetics recovers the broader context in which the conceptual innovations of the movement emerged and were worked over and contested. Galimberti’s scholarship is judicious, generous, and expansive while remaining politically committed, and it is theoretically keen while achieving a concision that enables it to cover a lot of ground. Perhaps most impressively, it manages to adopt the method of its subject by avoiding static oppositions and resurrecting a sense of the conflicts in motion. This is a strategy that acknowledges operaisti doyen Mario Tronti’s injunction that class is not something you can pick up off a table and throw around, but something you are always, inexorably, arriving at. Galimberti’s chapter on the Gruppo Immagine and the Wages for Housework Campaign touches on some of the themes explored in the writing above, bringing in their connection with gender, capitalism, and social reproduction. Well worth reading for those of us who feel it may be time for a renewed commitment to critique and to what Tronti called, with gorgeous concision, the “strategy of refusal.”

On the Playlist

There are tons of great stories about this song, but for now just listen to the bass.

Sean Sayers, “The Concept of Labor: Marx and His Critics,” Science & Society 71, no. 4 (2007): 431–54.

David Brody, Workers in Industrial America: Essays on the Twentieth Century Struggle, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 4.

Brody, Workers in Industrial America, 1.

Ronald W. Schatz, The Electrical Workers: A History of Labor at General Electric and Westinghouse, 1923-60 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983), 35.

Peter Ackroyd, Blake (London: Vintage, 1999 [1995]), 177.